Summary

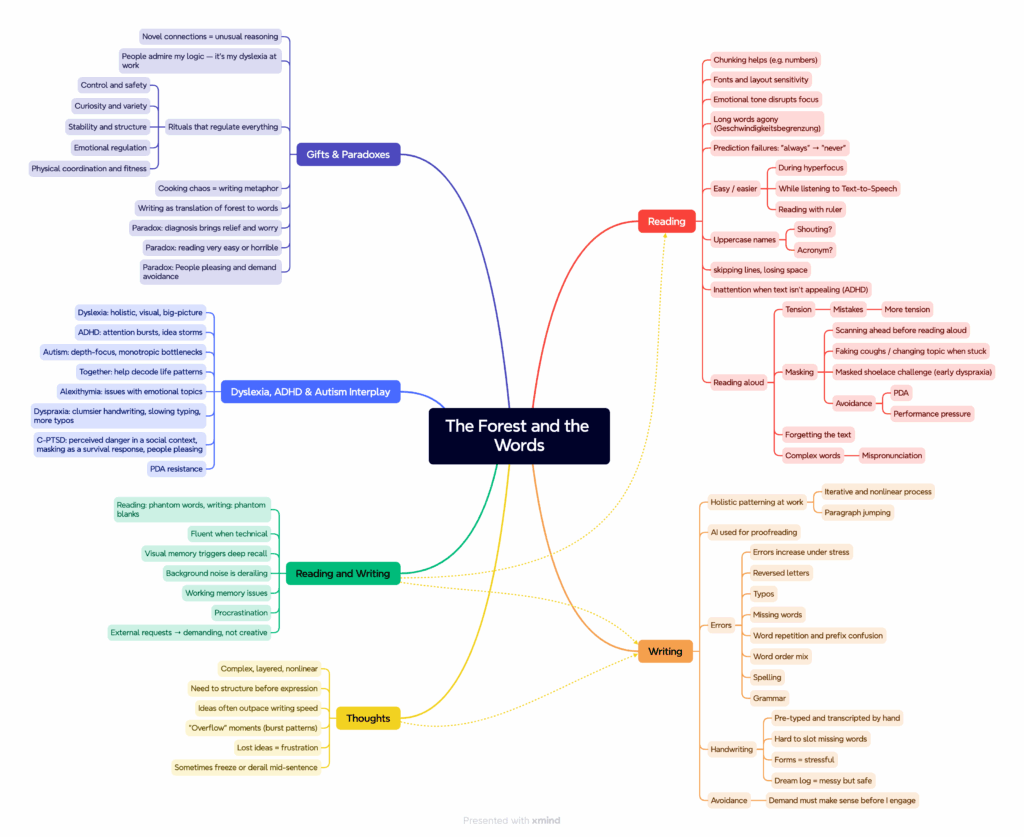

My reading and writing combine dyslexia-like traits (phantom words, skipped lines, sequencing challenges) with ADHD’s focus shifts — sometimes I hyperfocus and flow, sometimes I struggle at every step.

My writing, like my reading, is shaped by layered thinking — rich in ideas, but requires many iterations before it takes final form.

Early Signs… or Clever Masking?

I’ve been told I learned to read and write early, which makes my adult struggles feel confusing. But now I see that both can be true:

- I may have started early thanks to curiosity, pattern recognition, or supportive people.

- But my actual reading fluency and stability weren’t necessarily smooth — just masked by my memory, compensation strategies, or strong logic skills.

As for speaking, the story’s even weirder. One person says I was late to talk. Another says I had excellent speech when I started preschool. It’s possible I first learned a dialect that I no longer use — which might explain some of the confusion. Either way, that delay–then-fluency pattern fits the profile of someone who learns in bursts, not steps (and I detected this pattern in other areas).

In hindsight, it all makes sense — but only now that I’m zooming out far enough to see the full picture.

Reading

There are rare times when I can devour a book in hours, but I’m more likely to struggle to get through a single chapter for days. This fluctuation in reading ability is a constant challenge that affects my reading engagement. When I am given something to read, I don’t always know in advance how it will go.

The main factor that influences my reading is the way the text is shaped — its font, size, spacing, and structure. They have a huge impact on my reading comprehension, but that’s not all…

One of the most notable challenges I face is the phenomenon of “phantom words.” Sometimes, I imagine words that aren’t actually in the text, distorting the meaning and forcing me to re-read passages multiple times. Sometimes, the opposite also happens: a word pops out from the page, and an blink later I can no longer find it. I know it was there. I felt it. But it’s like it dissolved into the forest of the page. I’ll scan the paragraphs, feeling haunted by its absence, as if the word has turned into a phantom that was once real.

I can accidentally swap syllables or letters in a word or even a word from another part of the page, which appears misplaced. Additionally, I often skip words or entire lines without realising it, which can make comprehension difficult. This issue is exacerbated by dense paragraphs, where words can appear disordered or unclear, requiring me to carefully scan the page to locate specific terms. Losing track of where I am in a sentence or paragraph discourages me from reading on. My working memory also plays a role in reading. It feels like I have read and understood something, but an instant later, I forgot some key parts of it.

However, when I read technical texts, I notice that I’m much less affected by my usual reading challenges. It’s as if the technical language make the process smoother for me. The regularity and logical flow help me anticipate what’s coming next, so my brain doesn’t “trip” as often. I wonder if some of my phantom word errors in other types of texts are actually a side effect of my brain’s pattern-prediction system being tripped up by unexpected content or lack of structure.

Reading aloud feels like a high-stakes performance for me. The stress of reading in front of others creates a feedback loop: tension leads to mistakes, which in turn deepen the tension. To slightly mitigate this, I need to “preview” texts silently before reading them aloud. Without doing it, my confidence plummets, and I can physically feel and hear my voice shaking. I am deeply confused if there’s an unexpected word in the text which feels like reading nonsense. And if I happen to mispronounce new or complex words, this adds fuel to the fire. Once my stress level has reached a threshold, I can even have trouble connecting groups of letters with their correct sounds, and I freeze. This anxiety makes public reading a significant challenge. In addition, I will not remember what I have read in public because my attention was fully focused on the reading activity alone.

Interestingly, I find that reading technical or encyclopaedic texts comes more naturally to me than casual texts or fiction. The structured and precise language of technical writing seems to align better with my cognitive processes. However, emotive and descriptive language in fiction or personal communications can derail my focus, and then I forget the essential part of the text.

One of the more confusing things is when I read a sentence and see a word that isn’t even there — or worse, read the opposite of what’s written. For example, in a sentence I wrote myself — “my fluency has always been inconsistent” — I read it back as “never inconsistent” and immediately wondered what I had done wrong.

This kind of error isn’t about eyesight or comprehension. It’s like if my brain is predicting what should come next based on context or rhythm, and inserting a familiar or “logical” word like never instead of always. That’s why I sometimes misread things even when I know the content — and why reading new or emotional texts can derail my understanding before I realise what went wrong.

Background noise is another major obstacle to my reading comprehension, as slight other distractions can also hijack my focus– running water in a radiator or even my body noises can be enough to disturb. Using a finger or anything that can be defined as a ruler to track lines and words I am reading helps to some extent, but it doesn’t completely remove the challenges I face.

In addition, I find it very difficult to find information on a busy page, like a form or a timetable, unlike visual diagrams that feel more accessible.

And it’s not only about text; for example, long, unbroken sequences of numbers are much harder for me to read than chunked ones. A number like 80000008 is almost unreadable unless I split it up into groups — like 80 000 008. When there’s no internal pattern to catch, my brain doesn’t know where to land. If I don’t use my fingers to create small groups, I just can’t read those.

Adding to this, I’ve noticed that low light and small fonts amplify the problem — even with glasses. I have mild astigmatism, and in some conditions, it makes certain digits or letters (like 0 and 8, or 4 and 6) visually blur or become indistinct. It doesn’t cause reading issues by itself, but it amplifies existing struggles — especially when precision is needed.

Close numbers often confuse me. For example, at the intersection of the RAVeL bike routes 163 and 613; it’s like they interfere and it took me ages to notice the difference between the two numbers. But when they are seen isolated, I handle them well.

Oh, and the ultimate word trauma price goes to the German compound nouns: Geschwindigkeitsbegrenzung feels like a wall of letters crashing toward me. Without natural word chunks, my eyes get lost — I often need to pause, scan, or reread to figure it out. It’s very much like reading digits without separators: my brain needs landmarks.

Another intriguing aspect of my reading experience is that I find reading (and writing) in English to be less challenging than in my native language. The simpler grammar and syntax, along with the emotional detachment and pattern recognition involved in reading English, make it a more straightforward process for me.

I also encounter difficulties when I read someone’s name written using uppercase characters, which my brain often misinterprets as acronyms or shouted phrases. And I remember getting emails or instructions in which I understood every single word, but I still didn’t know what they meant.

Overall, my reading struggles are not isolated incidents but often combine to create a complex and challenging experience.

Text-To-Speech

On a positive note, something that has helped me to read better is using Text-to-Speech tools. When I follow along with TTS, I can read more fluently and even keep pace with it. It’s like having a reading partner that keeps my focus on track and reduces the stress of decoding.

What’s amazing is that even in adulthood, this multisensory reading helps:

- It aligns sound and text.

- It anchors my pace and attention.

- It lowers the pressure of “doing it all at once.”

And yes — I’ve found that using TTS doesn’t make me dependent. On the contrary, it improves my rhythm and confidence.

Writing and Typing

In Short

I do this:

- I hold a complex, layered thought structure (the forest).

- I work to translate the thought patterns into words (first iteration).

- I start to write, jumping between paragraphs, but each addition makes me realise other pieces need adjusting or clarifying (second iteration).

- I revisit the text and reorganise both the ideas and the words, sometimes several times (multi-layer iteration).

- I eventually decide the text is finished — not because it’s incomplete, but because I’ve chosen to stop at a point where precision feels “good enough” or may even become “confusing or too discursive” for an external reader.

- I try to correct typos, find missing words, and get it proofread.

When Thoughts Themselves Are The First Challenge

My writing difficulties aren’t only about getting letters or words in the right order. Before I even start typing, there’s another layer:

My thoughts are rich, complex, and often unsorted — like trying to hold a whole forest in my mind at once. When I’m outside my comfort zone, those thoughts get tangled up with distractions: new ideas, worries, or even random connections that suddenly seem important (and sometimes, they are).

The first real challenge is finding a way to structure these layered thoughts so they can fit into words. And when I do find the words, they don’t always show up when I need them. It’s like my brain knows what I want to say — but by the time I’m writing, the clear picture has already started to scatter.

Writing, for me, isn’t just about spelling or grammar. It’s about turning a multi-dimensional, fast-moving inner world into a linear string of words. And that’s a tricky business!

How I Build The Text in Layers, Not Paragraphs

I write in layers, not lines — shaping the forest, not planting one tree at a time. I jump between paragraphs — adding something here, which leads to a change somewhere else, and so on. Writing for me is an iterative process — not just for the words, but for the ideas themselves.

Meaning comes first; the form catches up later, with more errors as the cost, and sometimes I have to pause to reorganise my thoughts before I can continue.

That makes it slow, and it means more errors as I focus on the accuracy of meaning rather than the perfect order of letters or sentences. But it also means that when I do finish, the ideas behind the text are deeply thought through. If I decide a text is finished “sooner,” it just means I stopped after fewer layers of iteration — not that the writing is incomplete, like a half-written linear draft.

But for simpler text that doesn’t require reasoning as I write, I can work more sequentially.

I always thought that I was naturally writing in this way because of the lack of trust in my working memory, but the whole picture seems more complex since I realised that it’s my holistic patterning at work.

The Horror Show

I might skip a word entirely, or write things out of sequence, or type “form” when I meant “from” (or when I don’t lose the ‘f’ of ”shift”). Other times, I repeat small words without realising — like “the,” “some,” or “have.” I’ll only spot them on a re-read. I think it’s my attention jumping ahead while my fingers are still typing behind.

When I’m under pressure (like writing in front of others, or composing an important email), it gets harder. The more I want to get it right, the more my fingers seem to work on their own plan! When the text is unprepared, I usually freeze at that point.

When typing, I often reverse letters, forget whole parts of a sentence, don’t press the keys firmly enough, or end up with words in the wrong order. My dyspraxia probably joins the party here, making my fingers clumsier or slower than my brain. On top of that, spellcheckers don’t always catch the full extent of my errors.

And spelling? it’s like having a spell on me! There are words that I never manage to spell correctly, no matter how often I check them. Even when I know a word, I second-guess myself. I’ll stop to check it — only to find I had it right the first time. English prefixes like in, un, and dis? Absolute chaos. I have to double-check whether I’m unsettling or dissettling something. (Is “dissettling” even a word? Who knows.)

What I find funny is how something missing from my writing can create confusion. When I leave out a word (without noticing), people sometimes read between the lines — as if I meant to imply something secret or clever. In reality, I just forgot the word! It’s like my brain and my hands didn’t sync up, and I’m as confused by their reaction as they are by my sentence.

Sometimes, I also lose a word mid-sentence — which is more noticable speech. I’ll blank, describe it, or switch languages, and then (of course) the exact word pops into my head right after. It’s like my brain runs an invisible background process that finishes just a second too late.

I try to compensate by re-reading, but that’s often not enough. Thanks to the rise of AI, I can now ask it to proofread my text, but I don’t want them to do the complete writing exercise for me, otherwise my skills will probably worsen, and also, the text may not appear in the way I intended (both style and content). For professional and private texts, I installed some local LLMs on my home computer so the data stays local, but their processing takes a lot of time.

Handwriting: My Personal Adventure in Stress

Handwriting feels like a stressful adventure — no easy way to fix mistakes and no place to iterate. So I often start with a list of items that I need to write, and once I decide I’m done, there’s no way back, except restarting from scratch.

If I spot a missing word in a sentence, I can’t just slot it in. Filling out forms with a pen feels like a stressful adventure: I have to slow down, double-check every letter, and still worry that I’ll make a mistake that I can’t easily fix.

In the end, I only really use handwriting for things I keep private — like my dream log — where it doesn’t matter if it’s messy or full of crossings-out. If I write a card for someone, I always type the text first so I know what I want to say, but even then, writing it out by hand doesn’t come error-free.

For me, handwriting isn’t just slow or clumsy — it’s a task that takes extra concentration, planning, and energy every single time.

When the Mind Overflows: Patterns, Monotropism, and Idea Storms

Some of my biggest challenges with writing don’t come from language itself — but from how my brain generates and holds ideas. I often think in dense, interwoven patterns, not tidy sequences. My memory works best visually: a photo can unlock an entire day, and I naturally draw diagrams instead of describing things in words. For me, the whole structure exists at once, not line by line.

This can make writing feel like translating a map into a paragraph.

When I write technical or practical subjects, it flows easily — the structure is already present in my head. But when I need to write a summary or conclusion, it becomes difficult. Every point feels important. I don’t naturally rank ideas — they’re all part of the same interconnected shape. Monotropism (a deep autistic focus on one topic at a time) means I can go very deep, but switching focus to “wrap up” or “prioritise” can feel like exiting mid-dive.

And then come the idea storms. One thought sparks five more, which spark five more… and suddenly I’m flooded with concepts — faster than I can write them. It’s not just overwhelming, it’s frustrating, because I know I’m losing brilliant ideas as they come. (It feels like waking up after a dream and remembering the excitement, but not the dream itself.)

Sometimes, this overflow shows up mid-sentence. I might write something odd, or suddenly jump topics — not because I’m distracted, but because a stronger connection just popped up.

If you want to picture how it feels in my brain, imagine this:

The water is boiling over the pasta pot. The microwave beeps, spilling soup. The fridge is open, the window slams in the wind, and the cat meows to be fed — all at the same time. And I’m still trying to focus on chopping onions.

That’s what writing feels like when all my thoughts demand attention at once. But out of that mess sometimes come the most surprising ideas — if I can catch them in time.

Conclusion

When I try to answer multiple questions while writing in a linear way, I easily forget some of them.

So if I just answer your message with a simple “Okay”, or miss a point while answering your message, I’m not neglecting you, but either I’m just saving a considerable amount of energy and time, or I forgot a part of your message.

Links to Neurodivergence

As a curious troubleshooter, I had to dive into what dyslexia is. From my understanding, my reading struggles might partially be explained by a mild or a stealth dyslexia combined with ADHD’s focus instability + hyperfocus that creates a variable reading performance.

The other traits that shape the experience:

- Autism → systems thinking, depth seeking, structure craving.

- Dyspraxia → clumsier handwriting, slower typing.

- Alexithymia → regulating through structure/ritual rather than feelings, logical attempt to “feel the feelings” while reading.

The Other Side of Dyslexia

To simplify, dyslexia isn’t just about reading struggles — it’s a different way of processing information, where linear, step-by-step processing (especially in written language) is harder but pattern recognition, big-picture reasoning, or relational thinking feels more natural. Dyslexia can give exceptional skills in seeing connections others miss, reasoning holistically and problem-solving creatively. Those are traits that I initially associated with autism because of the overlap.

I looked at my rituals again with a new perspective, and I figured out that they are not random habits – they are a holistic system that meets my ASD, ADHD, C-PTSD, dyspraxia and alexithymia needs simultaneously. I find it amazing how my brain was able to architect such a complex system without even being consciously aware of either my needs or the way to satisfy them. I guess my life could have been miserable if I didn’t have my rituals in place. I now consider that dyslexia is a gift, and its associated reading and writing struggles are the cost, although I would probably reason differently if the intensity of my neurodivergence traits were stronger.

I’ve often been told by others that they admire my reasoning capabilities. They are often bound to linking ideas, concepts, or solutions that don’t obviously go together, seeing odd analogies, or inventing original hacks and workarounds; and I found out that those capabilities are associated with novel connections, a common trait associated with dyslexia.

People admire my reasoning, and I’ve learned that it’s my dyslexia at work — they’re praising the very patterning style that also scrambles my spelling. Dyslexics really do have more fnu.

The link to my self-discovery

Sorry, this section is out of scope, but until I create a dedicated page, it’s the best place where it can fit.

I find it amazing that it’s actually my autism and dyslexia together that may have allowed me to discover my own neurodivergence.

I holistically mapped patterns across years of life data — habits, preferences, quirks, challenges, strengths — and how they fit together into a coherent framework.

I connected dots between experiences others might have seen as random: clumsiness here, balance distrust there, social struggle over there… and I saw the underlying architecture.

For example, I have a negative experience with archery, and when I told a friend, they replied that it was an irrelevant experience, but in reality it was a point on the map. It wasn’t just “I didn’t like it”, but “my brain-body coordination couldn’t connect in that context — that means something.” And I wondered why (but it took me several years until I looked into it).

My autism contributed the systems thinking, the drive to pattern-match, the passion for detail and coherence, and the need to understand the deeper “why.”

My dyslexic cognitive style contributed to the holistic big-picture grasp, the ability to see surprising connections, and the intuition to link experiences that seemed scattered on the surface

During the process, I had to speculate, but like good market speculators, it wasn’t random: I had a pattern basis and a fail condition; if the analogy didn’t fit, the output would have fallen apart.

Every time I nearly derailed, it wasn’t because I was wrong, but because there was a missing piece on the map (alexithymia, fawning, context of childhood environment). Each discovery straightened the path because it filled those gaps.

Together, they gave me the tools to decode my life in a way that might not have been possible through only one lens. It feels like my brain acquired those patterns long before I knew what to call them.

Behind the scenes

It took me about three weeks to complete this document. I experienced some frustration, felt silly, got interrupted and gave up for the day several times, didn’t like the growing structure and also procrastinated the reorganisation, but also during the writing, I explored the topic deeper and discovered some missing points that required me to review some other parts of the document. I am unable to say if my frustration has led to some anxiety, because of (or thanks to) my alexithymia.

But there’s another paradox in my writing; when I document something, it stays in my long-term memory. I don’t know if that’s due to the numerous struggles during the writing exercise that I had to review it under different angles, or the repetitive attempts to document it, or simply because the ‘or’ isn’t exclusive.

I’ve learned how to describe my reading traits using matching patterns, but I dove deeper into their details when I decided to document them. Hadn’t I done this exercise, I would still be describing my reading experience as inconsistent without understanding why.

The Mask Behind the Book

Looking back, I realise I used several unconscious strategies at school to mask my reading struggles — especially during classroom reading exercises.

When the class took turns reading aloud, I would scan ahead and try to pre-read the section I expected to be called on for. This gave me a chance to decode tricky words in advance — and avoid the panic of sounding them out on the spot.

Sometimes, if I hit a roadblock, I’d stop and ask what a word meant — not because I didn’t understand it, but because it bought me time to reset and regain control. Other times, I started coughing. These weren’t just delays — they were ways to cope.

At the time, I didn’t recognise these as survival strategies — I just knew I needed to “buy time” to avoid embarrassment. Today, I see them as part of my broader pattern of masking: trying to hide my difficulties with grace, even when it meant pretending nothing was wrong.

It’s not shameful. It was adaptation. And understanding why I did these things brings me more compassion than I ever gave myself in the moment.

Masking didn’t start in my teenage years. It began as quiet, invisible problem-solving in early childhood.

It wasn’t the only time I masked something that felt shameful. Years earlier, I remember being unable to tighten my shoelaces — for years. Every time we had swimming class, I feared putting my shoes back on. I knew I needed help, and I’d quietly try to find an adult before anyone noticed. I was terrified that other kids would discover it.

That moment — needing to hide something so practical, so visible — was probably my first real experience of “half-masking”: covering a difficulty just enough to avoid exposure, but still carrying the stress, the workaround, and the shame.

Updates

How The PDA/Fawning Paradox Affected My Reading & Writing

Sometimes I’ve felt torn between two opposing forces:

a need to say yes to others (people pleasing),

and a need to say no to demands (even small ones).

That paradox can show up in how I respond to reading and writing tasks —

not based on difficulty, but on how I was asked and what it represents.

My people-pleasing habits may have made me less likely to express reading difficulties — especially if I feared being judged or disappointing others.

Sidebar: Compliance Without Sincerity

Once, I was asked to write a document I knew no one would ever read.

So I filled it with Lorem Ipsum. Pages of it. Just to see if anyone would notice.

No one ever did.

It was my way of “saying no” without actually saying it —

and protecting my time and energy without breaking the mask.

This was a demand-avoidant act in fawning disguise.

Pronouns: Tiny Words, Big Confusion

Sometimes, pronouns like she, they, it, or this are harder for me to follow — especially when there’s more than one person, idea, or object involved.

- When reading, I can lose track of who or what a sentence is referring to. Ella looked at Maria and said she wasn’t ready.

Wait — who wasn’t ready? (I had to read it twice!) - When writing, I worry that people won’t know what I meant when I use “it” or “they.” So I often rephrase for clarity, or end up over-explaining.

This isn’t just a quirk — it may be tied to autistic detail focus, ADHD working memory limits, or dyslexic language processing patterns. It’s one of those small invisible struggles that slows me down and adds cognitive effort — even in simple texts.